There’s Nothing 'Micro' About the Impact of Microaggressions

August 12, 2019by Katie Smith

What is a microaggression?

A white woman walking home crosses to the other side of the street as she approaches

a black man. A physician assumes that a person who appears to be homeless and says

she is in pain is seeking narcotics. A professor compliments an Asian American medical

student’s perfect English, even though it’s his first language. These are microaggressions:

small acts of prejudice that insidiously reveal the speaker’s bias and impact the

lives, careers and health of the recipients.

“Microaggressions are seemingly harmless to outsiders because of the assumptions we

make,” says La-Rhonda Harmon, PsyD ’18, who specializes in curriculum development and workplace training in social service

settings. “In school or the workplace, microaggressions are dangerous because they

marginalize and ultimately underutilize talent, impair recruitment and retention,

erode an individual’s performance, stifle innovation and growth, inhibit teamwork

and collaboration, and adversely affect business growth.”

Columbia University psychologists define microaggressions as “brief and commonplace

daily verbal, behavioral or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional,

that communicate hostile, derogatory or negative slights and insults.” In contrast

to overt racism, microaggressions are smaller, baked into daily conversation and often

passed by without notice or bystander intervention.

Do microaggressions happen in health care?

While many microaggressions in healthcare settings are similar to those experienced

in every part of life, the power dynamics are drastically different for patients.

“Healthcare microaggressions occur when clinicians make unfair judgments and assumptions

about individuals from minority groups,” says Dr. Harmon. “Invariably, these experiences

compromise patient-centered care and inhibit the potential for mutually respectful

patient-clinician relationships.”

Dr. Harmon offers as an example a clinician who berates a patient for noncompliance

without acknowledging systemic factors such as financial or familial stressors. In

response, the patient feels judged and may avoid future treatment. “It is imperative

for healthcare settings to provide ongoing cultural competence training and supervision

to improve patient engagement and healthcare outcomes for individuals from minority

groups,” she adds.

- A study from the University of Washington’s Surgical Outcomes Research Center found

six common microaggressions reported in healthcare settings: mistaken identity, mistaken

relationships, fixed forms, entitled examiner, pervasive stereotypes and intersectionality.

Read more.

- Of the 150 American Indian patients surveyed by the University of Minnesota, over

36 percent reported experiencing microaggressions in health clinics. Read more.

- A study from the University of Colorado Boulder finds that “clinicians’ implicit bias

may jeopardize their clinical relationships with black patients, which could have

negative effects on other care processes. As such, clinician bias may contribute to

health disparities.” Read more.

- A 2014 study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine found that racial microaggressions accelerate aging at the cellular level. Read more.

- In 2015, researchers from the University of Tennessee “found that microaggressions

can trigger intrusive memories of traumatic racially related incidents. This supports

that for some, microaggressions are experienced as traumatic events, which is of serious

concern. Many of the same principles used to care for survivors of abusive trauma

might be adapted to explore and intervene on effects of racial microaggressions, referred

to as trauma-informed care.” Read more.

What can healthcare providers do?

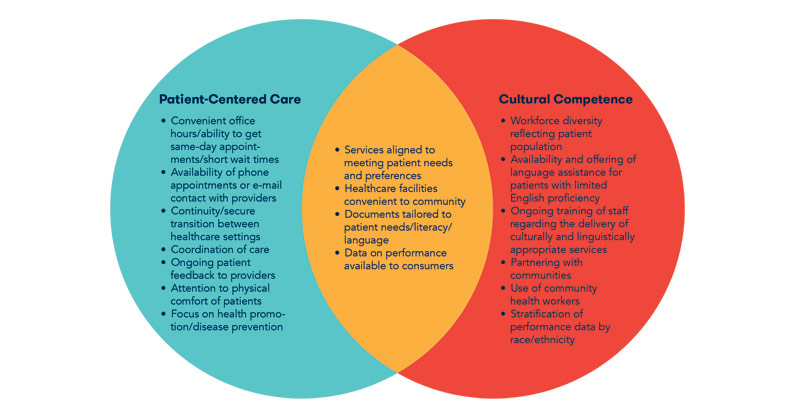

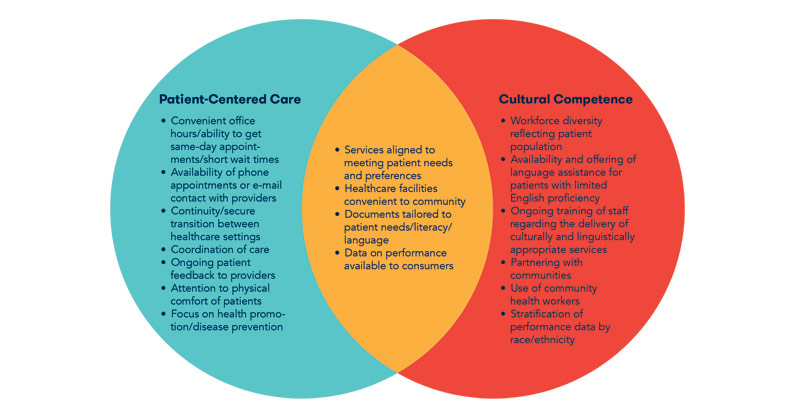

In response to evidence indicating that negative relationships between patient and

provider lead to adverse health outcomes, there has been a push toward culturally

competent care that places the patient at the center. Service providers are encouraged

to see “through the patient's’ eyes.” Hallmarks of culturally competent, patient-centered

care include services that meet patient needs and preferences; healthcare facilities

that are convenient to the community; documents that are tailored to patient needs,

literacy and language; and data on performance available to consumers.

Taking action

The A.C.T.I.O.N. Method by Cheung, Ganote and Souza (2016) suggests that microaggressions

be addressed in six steps:

- Ask clarifying questions.

- Carefully listen.

- Tell others what you observed that was problematic.

- Impact consideration for yourself or potential others.

- Own your response.

- Next steps.

What is the impact of microaggressions?

A 2013 article in the Journal of LGBT Youth called microaggressions “death by a thousand cuts.” One discriminatory experience

is horrible. How can you measure several, every day, over the course of an entire

life? For some, the impact can be deadly.

- Research suggests that experiencing microaggressions leads to elevated levels of depression

and trauma. Read more.

- A study of 405 young adults of color links microaggressions to suicide risk. Read more.